Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor-in-chief of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Is immigration good or bad for a country? This question still seems unnecessary to me. it depends on the country. Even if we ask the question purely in economic terms, things vary. Immigration adds millions to some countries’ coffers, but has a more ambiguous, even negative, impact on others.

To take a few more specific examples: the rise in gun violence in Sweden, attributed by police to gangs led by second-generation immigrants, is bad. On the other hand, the fact that immigrants and their children are systematically over-represented among successful business founders is a good thing. Covid-19 vaccines, not to mention the technology behind them, are the product of immigration.

But a striking trend emerges when we look at where these different impacts are concentrated: almost everything seems better in English-speaking countries. Immigrants and their descendants in the UK, USA, etc. tend to be more qualified, have better jobs and often earn more than the native-born, while those from continental Europe fare worse. In terms of tax impact, immigrants pay more on entry than on exit in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Ireland, but are net beneficiaries in Belgium, France, Sweden and in the Nederlands.

Language and geography undoubtedly play a role. English-speaking countries benefit from a large global pool of educated English speakers and fewer land borders, allowing them to better control who enters the country. But outcomes for immigrants and the society they settle in do not simply depend on the language and skills upon arrival. Some countries are much better at creating environments that allow people from different backgrounds to integrate into the economy and wider society.

Education policy expert Sam Freedman points out that in Britain, second-generation children from poorer Bangladeshi communities perform better academically than the average white British student, while black Britons are more likely to attend college than their white counterparts. In the United States, children of foreign-born parents are now more likely to attend college than those of native-born parents. In France, on the other hand, students of North African origin have much less chance of progressing in their studies.

What is even more striking is how things have changed over the generations. The children of immigrants in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada all experienced smaller racial wage deficits than their parents, but most second-generation immigrants in France and Germany regressed. Similarly, the poverty rate among immigrants has fallen over the past decade in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and Canada, but has increased in France, Sweden and the Netherlands.

This marked divergence may be linked to the failure of integration policies in much of Europe. In France, decades of social exclusion and hostile policing have created deep-rooted inequalities. In Sweden, a policy placed all immigrants on benefits by default, while housing policy promoted segregation. Today, Swedish immigrants have an unemployment rate three times higher than that of natives, the largest disparity of any developed country.

Studies show that this lack of progress between generations is particularly harmful. First-generation immigrants are less involved in crime than native-born citizens. But in his book Undesirables: Muslim immigrants, dignity and drug traffickingGerman ethnographer Sandra Bucerius describes how, while second-generation immigrants in the United States and Canada continued to have lower levels of crime than the native-born, in Germany crime exploded among the second generation.

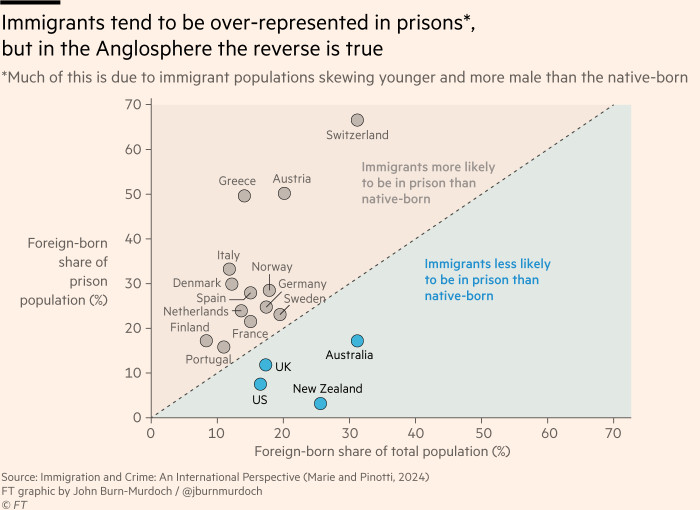

International comparisons reveal that people with immigrant backgrounds are generally incarcerated at similar or higher rates than native-born people, except in the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia. , where they are under-represented in the prison population, a sign of successful integration.

In everything from education to employment, income to crime, the Anglosphere seems to have figured out how to make immigration work at least reasonably well. This is reflected in public opinion: continental Europeans are more likely to say that immigration has been bad for their country, according to figures from Focaldata.

To be clear, the ongoing and unedifying debates around immigration in the UK and US demonstrate that, even when successful, this approach remains controversial. Hard evidence may indicate benefits; a large part of the public is still not convinced. But in a world where countries are increasingly competing to recruit skilled migrants to boost their demographics and economies, the Anglosphere seems well placed.

[email protected], @jburnmurdoch

This article has been updated to correct a sentence about racial differences in education in the United States.