A reader asks:

I know that it is not possible to consistently time the stock market. But what about the bond market? The Fed is expected to raise rates throughout 2022 and possibly 2023, then cut them again in the near future (possibly before the election). Isn’t the following strategy easy to win: buy when rates become “high”, sell when they return to 0%? I know these cycles aren’t supposed to be as short as they are right now, but I don’t see a lot of focus on this strategy and this segment.

The bond market is certainly easier to handicap than the stock market in many ways.

Bonds are more driven by math than the stock market.

You can try to predict stock market returns using a combination of dividends, earnings, GDP growth, or a whole host of other factors, but predicting investor emotions is impossible.

And investor emotions, for better or worse, determine valuations and how much investors are willing to pay for certain levels of dividends, earnings or GDP growth.

For example, profits grew by nearly 10% a year in the 1970s, but stock market returns weren’t great. Revenues grew by less than 5% per year in the 1980s, but returns were fantastic.

Stock market timing is difficult because it is difficult to predict the short term and sometimes the long term.

The long-term yields of high-quality bonds are quite easy to predict because the most important factor is known in advance: the starting yield.

This graph shows the starting yield of the 10-year Treasury bills as well as the resulting annual 10-year yields:

It’s a pretty clean board. The correlation between the starting yields and the 10-year yields is 0.92, which means that there is a very strong positive correlation here.

If you want to know what your future bond yields will be 5-10 years from now, the starting yield will get you pretty damn close.

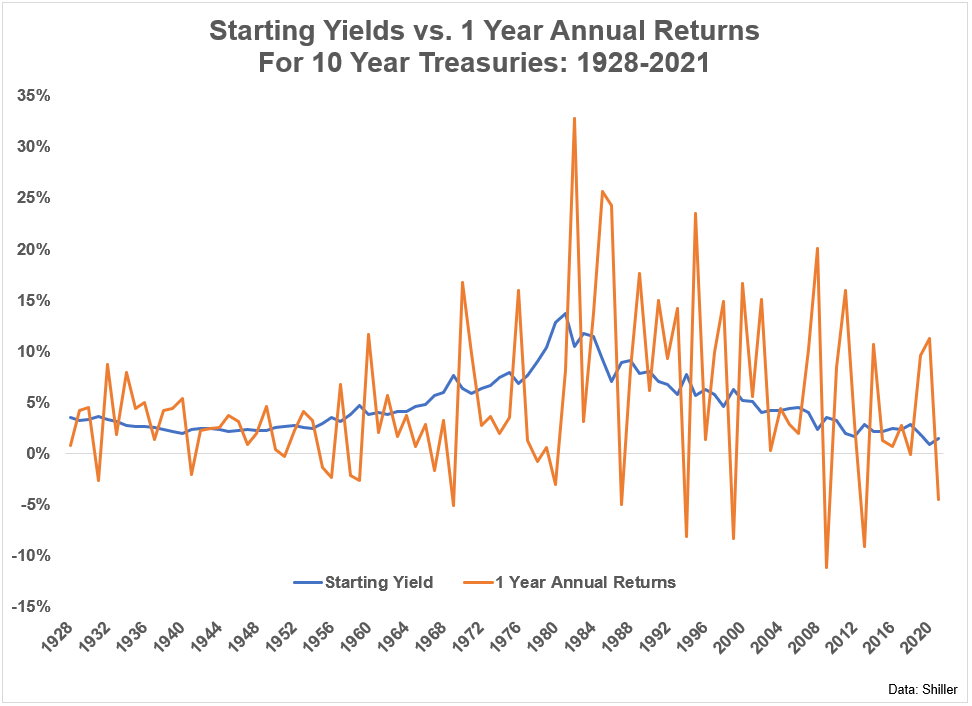

The problem is that it is not so easy to predict what will happen to bonds in the meantime. Just look at starting returns versus one-year returns over that same time frame:

It’s all over the map due to changing interest rates, inflation, economic growth and investor preferences.

While long-term bond yields are ruled by math, the short term is always ruled by emotions and economic uncertainty.

It is extremely difficult to time the market, so if you want to do it, you need rules in place. The problem is that execution will likely be difficult if the bond market does not cooperate with your metrics.

Let’s say you decide to buy bonds when rates reach 5% and sell them when rates drop below 1%. This seems like a pretty reasonable model given how the market has evolved.

This range looks pretty good right now, but what if it’s completely disabled in the future?

What if the yield ceiling is much higher than we currently think?

Or if the ground is higher?

What if 0% was no longer the case for a while during a slowdown?

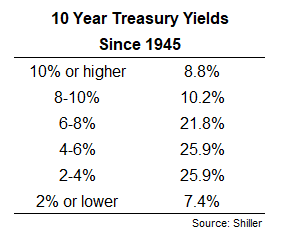

I looked at the distribution of 10-year Treasury yields since 1945:

Returns were only 4% or less about a third of the time. It’s possible that rates are set to stay much lower for much longer, but that’s certainly not guaranteed.

What happens if rates are stuck in a range of 2% to 6%? Or 3% to 7%?

In this case, you end up buying too early and never hitting your sell trigger. It seems possible that the Fed will have to cut rates in the next recession, but I don’t know what that new level will be.

I think investors will need to be more careful about their fixed income exposure going forward.

In a more volatile interest rate environment, you need to be more careful about duration, credit quality and the shape of the yield curve when determining what you want out of the bond side of your portfolio.

Every position in your portfolio should have a job and the same goes for fixed income securities.

Are you looking exclusively for performance?

Do you prefer stability?

Are you in the market for total returns (income + price appreciation)?

It’s more important than ever to define what you’re looking for when it comes to bond exposure.

If you prefer to keep volatility on the equity side of your portfolio, short-term bonds seem like a pretty good deal right now.

If you want to be more tactical, it might make sense to take more duration now that rates are higher and the Fed might be pushing us into a recession.

But it’s important to remember that trying to time the bond market could add even more volatility to your portfolio and not in a good way.

Timing the bond market is probably easier than timing the stock market, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a slam dunk.

Long-term bond yields are much easier to predict than short-term yields.

We talked about this question in the last edition of Portfolio Rescue:

Michael Batnick also joined me to discuss questions about municipal bond funds, news about uncertainty during bear markets, finding a new job to be closer to family, and some thoughts on life. buying a home in a tough real estate market.

If you have a question for the show, email us: [email protected]

Further reading:

Expected bond yields are finally attractive

Here’s the podcast version of today’s show: