In April last year, a group of almost 60 EU officials traveled to Sweden on a fact-finding mission to meet with Nasdaq Stockholm, the country’s highly successful stock market operator.

During a two-hour session on “capital markets ecosystems,” exchange executives explained why so many small and medium-sized companies decide to list on the Stockholm Stock Exchange.

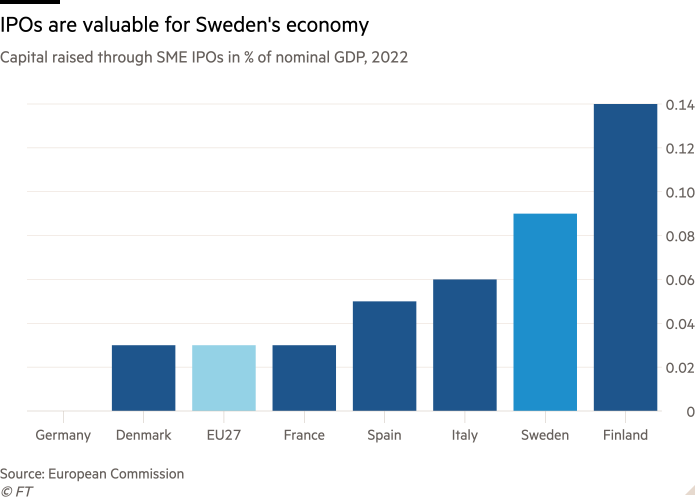

At a time when the UK and many other European countries are struggling to attract IPOs and suffering from falling trading volumes, Sweden stands out, relative to its size, with capital markets thriving, supported by legions of investors and which are even tempting foreign companies to list on the stock exchange.

“Sweden now has the deepest capital markets in Europe,” said William Wright, co-founder of markets think tank New Financial. “What they realized is you need this ecosystem and you need to encourage it every step of the way.”

European policymakers are urgently trying to revive their own stock markets by changing listing rules and incentives for business founders, and trying to encourage pension funds and retail investment in domestic stocks.

Yet Sweden already has a considerable head start over other countries, having introduced many of these measures years, if not decades, ago.

Over the past 10 years, 501 companies have listed in Sweden, more than the total number of IPOs in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain combined, according to Dealogic data. The United Kingdom comes first with 765 registrations.

While total IPO fundraising volumes in Sweden are much lower than in the United States – where some large Swedish companies such as music service Spotify and drinks maker Oatly have listed – the Nordic country has been very successful in encouraging small domestic businesses to stay home, encouraged by the depth of its stock market.

“Compared to the size of the country and also the size of the stock market, the [Swedish] The IPO market has certainly been more dynamic in allowing smaller companies to go public than others,” said Tony Elofsson, chief executive of Carnegie Group, a Nordic bank and asset manager. About 90 percent of listings are valued at less than $1 billion, according to Adam Kostyál, president of Nasdaq Stockholm.

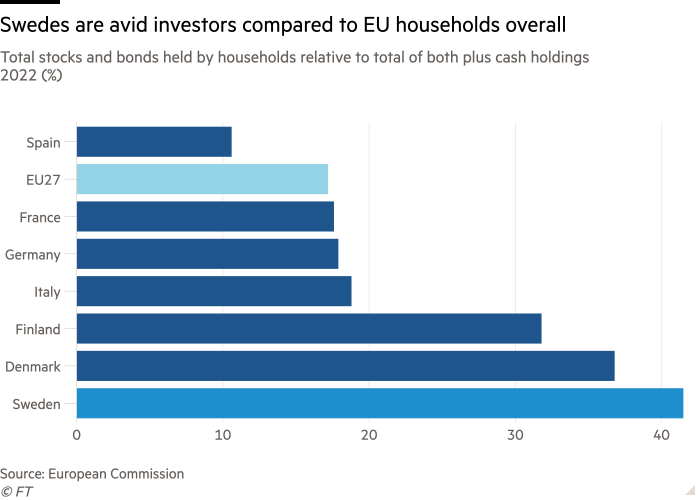

A key factor has been the country’s investment culture, which Carnegie’s Elofsson says has attracted “everyone from the man in the street to highly engaged investors in private banks to entrepreneurs , but also the community of small and mid-cap investors,” referring to institutional investors.

Among large investors, Swedish pension funds have long held domestic stocks. The nation’s four largest pension plans have generally maintained or increased their holdings of domestic stocks in recent years. In the UK, by contrast, pension funds’ domestic equity holdings fell by around 4 percent. Meanwhile, Swedish insurance companies hold the largest holdings of stocks in the EU.

Large investors typically play the role of anchor investors in IPOs, according to John Thiman, a partner at the law firm White and Case in Stockholm, giving confidence to companies preparing to go public and others investors.

“Every successful IPO has involved some level of anchor investors,” he said. “There is very strong sentiment towards stocks from rock-solid investors. »

Retail investors are also big buyers of Swedish stocks, helped by numerous reforms over the past decades. Compared to the rest of Europe, Swedish households have the highest proportion of their investments in listed companies and one of the lowest in terms of bank deposits, while their financial knowledge is higher than that of the Germany, France or Spain.

In 1984, the government introduced Allemansspar, a product allowing ordinary Swedes to invest in the stock market. By 1990, there were already 1.7 million such accounts, helping to launch domestically focused small and mid-cap funds.

Such funds came “10 to 20 years before any other country did something similar, at least in Europe,” said Carl Rosenius, head of capital markets at Swedish bank SEB. “This is certainly the success story in Sweden, where large funds are actively seeking domestic small and mid-cap opportunities.”

Rule changes in the 1990s allowed citizens to invest 2.5 percent of the amount they allocate to their retirement in funds of their choice, supported by a public information campaign.

And in 2012, the state introduced investment savings accounts called ISK that allow individuals to invest without having to declare their assets or worry about capital gains or dividend tax. Instead, the entire value of the account is taxed – and in 2024 it was around 1 percent.

Some charities visit schools to educate young people aged 16 to 18 about finance, for example about the difference between stocks and mutual funds, according to Joacim Olsson, chief executive of Swedish shareholder group Aktiespararna .

Other European countries are rushing to encourage their populations to invest in stocks. The UK launched a £5,000 tax-free allowance to invest in British businesses last month, while France’s finance minister, frustrated by the pace of EU reforms, called on some countries to move forward alone and create a new investment product.

“The real key lies in directly or indirectly mobilizing the participation of individuals and long-term investments,” said Sandro Pierri, president of the European Funds and Asset Management Association. “Sweden is absolutely a model in this regard.”

Nasdaq Stockholm has even tried to attract foreign companies, for example small and medium-sized companies in Germany, which, according to Kostyál, are “underserved in terms of the local IPO market”.

“It is clear that Germany has an infrastructure problem in that it is very difficult for small companies to list there,” said Joakim Falkner, a partner at Baker McKenzie in Stockholm. German investors have always preferred bonds to stocks, making fundraising more difficult.

Myles Murray, founder of Irish medical equipment maker PMD Solutions, opted to conduct an IPO in Stockholm earlier this year, saying the plethora of comparable healthcare companies listed there meant analysts could evaluate your company more easily, compared to a listing on Euronext Dublin.

Access to large investors was a big help. “We were a foreign, for-profit company, and the smallest broker could get an appointment with [the big pension funds] and it was very surprising,” Murray said.

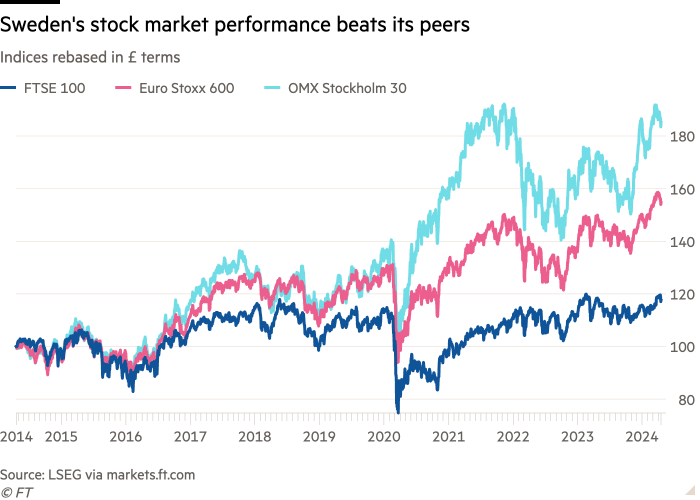

The Swedish system appears to have resulted in stock market returns. Its main index has gained 85 percent over the past decade, while the Euro Stoxx 600 index has risen 49 percent and London’s FTSE 100 just 17 percent.

This also helps convince small and medium-sized Swedish businesses to stay at home.

“Why cross the river to get water, as they say in Sweden,” said Elofsson of Carnegie.