Oil paintings have been a staple of the artist since the Renaissance, and in paint tubes for almost 200 years – using mainly linseed oil, derived from the flax plant. But for Iranian artist Amin Roshan, crude oil would ultimately be his tool of choice.

Roshan was born in 1982 near the first oil well drilled in the Middle East, in Khuzestan province, in southwest Iran. Although his family has worked in the petroleum industry for generations, including his grandfather, father, uncle, cousin and brother, Roshan broke that tradition to become an artist.

And now, after growing up with oil, decades later, he paints them.

In his Fire of Love exhibition, at the small Rossi & Rossi Gallery in London until March 27, Roshan finds links between the modern history of oil in Iran, which began in 1908, and ancient traditions, such as the worship of fire, which inspired the title of the exhibition.

Childhood inspiration

The “Naftoon” district of the city of Masjid-i-Sulaiman, where he grew up, was close to the Iranian and Iraqi borders. It was there that the British, who helped overthrow an elected government of Iran in 1953 rather than losing their grip on its oil, weakened their imperial muscles at the start of the 20th century.

“My shoes were stained with oil. I used to go home and wipe the stain with difficulty, because the crude oil was very difficult to clean”

– Amin Roshan

The early British influence – symbolized by the figure of Winston Churchill, who converted the British naval fleet from coal to oil – was so widespread that British words even entered tribal languages.

But the large houses built by the British eventually became the property of the Iranian National Oil Company and were allocated to its employees. Roshan’s grandfather first worked for the British, and most family members later spent their lives in commerce.

Behind Roshan’s childhood home, a thin skin of oil floated on the water of a stream and he grew up playing between the pipelines. “It was always embarrassing for me and my shoes were stained with oil. I used to go home and wipe the stain with difficulty, because the crude oil was very difficult to clean. In other words, it must first be washed with refined oil, then it must be washed with detergents. ”

After their move, he would always find himself drawn to his childhood landmarks for inspiration, according to the catalog of the exhibition which contains a statement by the artist: “I was six when my family left the city at because of the release of toxic gases, to go and live in Ahwaz, 145 km. But from ten years old, I spent all my summers with my uncle in Masjid-i-Sulaiman and I often played with my cousins in the streets where we lived. ”

“It is not easy to say why I chose oil as the theme for my latest collections,” writes Roshan in the catalog. “Being born into a family working in the oil industry and living in oil-rich land is not the only answer. The main reason may be its excessive impact and influence not only on my life and family, but also on the geography of Iran. “

“Oil is an integral part of global society today,” said Janet Rady, who organized Fire of Love – Roshan’s first solo exhibition in London. “Crude oil as a physical material is readily available in southern Iran and lends itself as the perfect medium for getting its message out.

“Many artists working in the Middle East are naturally drawn to comment on the socio-political issues that affect their daily lives.”

In one section of the exhibit, Roshan’s historical ties are highlighted through objects, including a British-made petroleum worker helmet and a gas torch, which are decorated in the style of traditional Iranian ironwork.

The engravings and paintings on the walls behind are atmospheric, evocative and full of spirit. Surreal scenes in the desert evoke the history of oil exploration, but also the Bakhtiari tribal heritage of his family, dating back thousands of years for a people who earned their living first from farming or carpet weaving.

Its use of vintage British maps and plans as a document reflects the early British role in the exploitation of oil-rich land.

Roshan also blends in nostalgic photographs of personalities and political leaders of the time, using crude oil, and sometimes tea, as a paint.

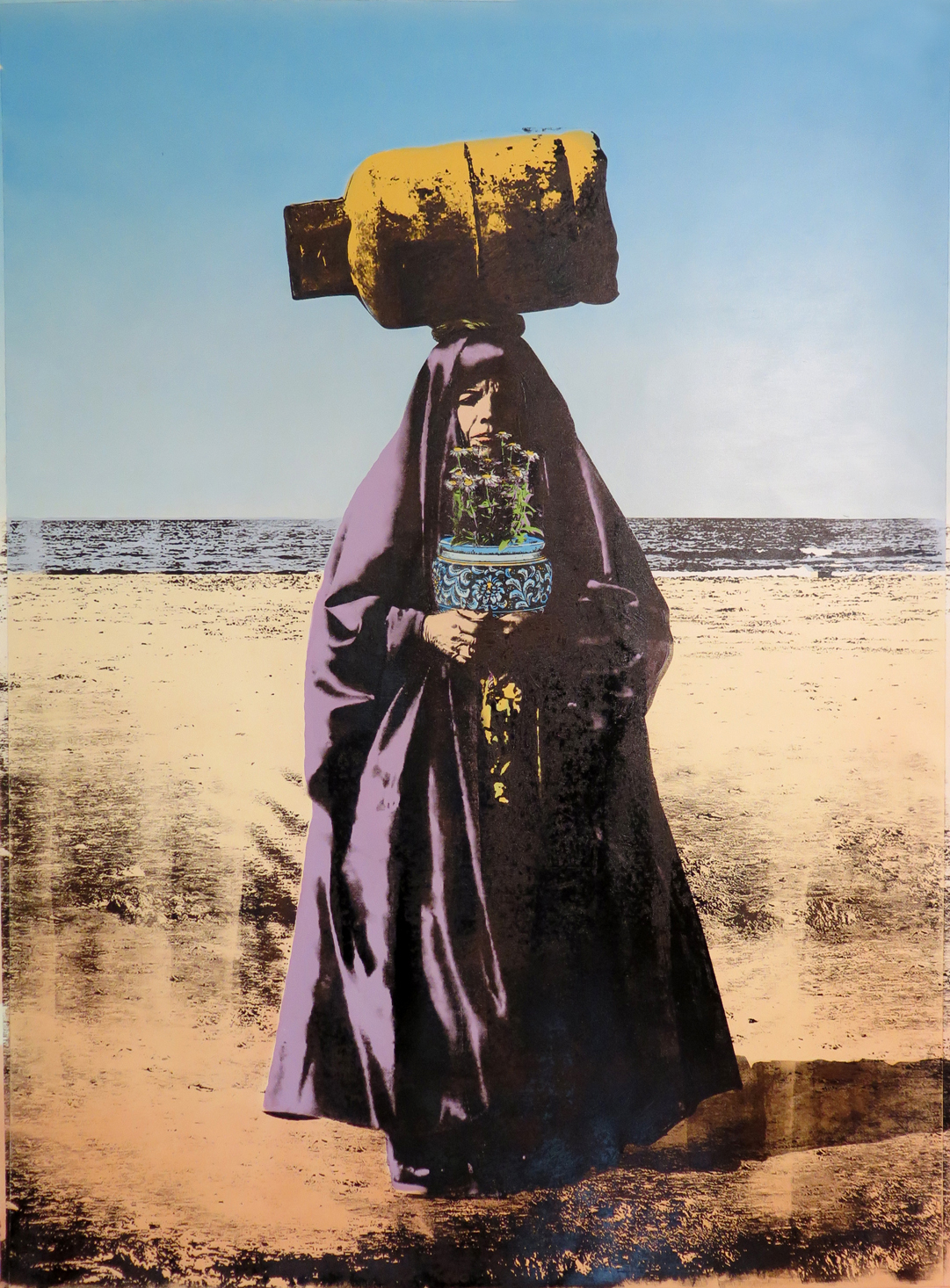

In her striking images, like hand-colored postcards, a woman in a bright purple dress stands in the desert by the blue sea with a bottle of bright yellow gas on her head. Women and tribal elders gather in a landscape dotted with desert plants, palm trees, oil barrels and jet planes, in enhanced artificial colors reminiscent of Andy Warhol, an artist Roshan recognizes that he is inspired through.

Artists attracted to oil

Roshan is not the only modern artist to make art in black gold. In 1977, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art opened in Iran. It included a collection of modern masterpieces acquired after the 1973 oil crisis that made the government of the Shah rich, but weakened art prices.

When the Shah of Iran came to open the museum, he reached out and tapped his fingers on the surface, a gesture of impatient curiosity that left the royal fingers covered with the black ink source of his wealth.

Japanese artist Noriyuki Haraguchi had installed a pool of reflective black oil, which still sparkles from the basement to the open floors of the building.

More than 40 years later, those present still remember how, when the Shah of Iran came to open the museum, he reached out and patted his fingers on the surface, a gesture of impatient curiosity that left the royal fingers covered with the black ink source. of his wealth.

Haraguchi recently returned to Iran to restore the work, clean up debris and refill the oil. Another Haraguchi oil deposit belongs to the Tate Gallery in London.

Another artist working with crude oil is Richard Wilson, whose famous installation 20:50 was bought by famous British art collector Charles Saatchi. It is a sump oil tank used at the waist, again a sparkling reflective black pool, but with a gangway in the center. Exhibitions of this work have drawn queued crowds around the world.

Although the British painter and sculptor Piers Secunda made an international reputation by making bullet hole casts in war zones in Afghanistan and Iraq, it was after reading The price, the Pulitzer Prize winning story in the petroleum industry by author and energy expert Daniel Yergin, that he also started working in petroleum.

Secunda produces nostalgic and photographic prints of famous places and characters from the first oil industry using oil from the places he shows. Boom town, for example, is a panorama of Burkburnett, Texas, from the name of the film inspired by the history of the “world oil field” with more than 850 wells in 1919.

Other images show the first cars and planes with their pilots and pioneer pilots, and the oil fields and their first inhabitants from Oklahoma to California. The great meeting, meanwhile, is a nostalgic image of the wartime meeting between King Abdulaziz Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia and President Franklin D Roosevelt aboard USS Quincy at Great Bitter Lake, Egypt, February 14, 1945.

The first meeting between an American president and a Saudi leader cemented a new strategic relationship as it became clear that Saudi Arabia was going to become a huge oil producer.

Working with oil

Secunda has a locked collection of oil samples from around 25 different locations. “I use materials directly derived from what is described or from the place,” said Secunda. “It brings the outside world into the studio. A material that powers everything we do all day, it reconfigures your way of thinking and looking at the work of art, because it is impossible to consider the subject without considering the oil first.

Before using the oil, a preparation is necessary. “To thicken it, I cook it,” said Secunda. “And I can cook a very small amount very, very quickly to about a third of its volume, and it’s a smelly process.”

Secunda notes that even acrylic paints – the quick-drying, brightly colored variety, beloved by amateur and professional artists and much easier to use than traditional oil – consist of around 50 to 60 different chemicals almost all derived from crude oil. “When it hardens, it’s like plastic,” he said.

“Crude oil is the most flexible and plastic material I have ever worked with. It has a sweet smell like essence with a texture like flowing molasses’

– Soheila Sokhanvari

The Anglo-Iranian artist Soheila Sokhanvari, who left Iran in 1978, makes nostalgic crude oil “drawings”.

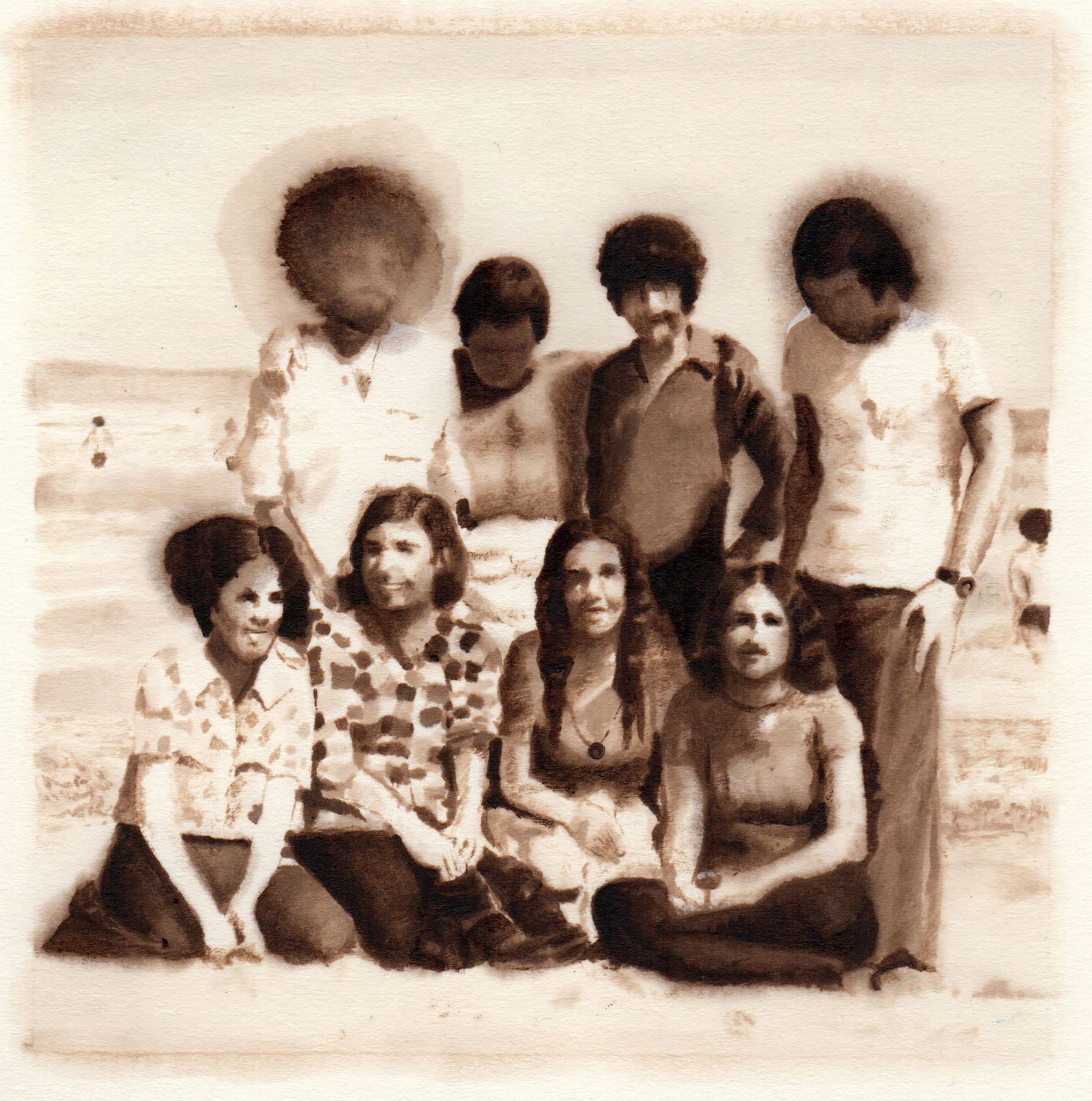

His work is inspired by family photographs or media images dating from pre-revolutionary Iran, characters in dark tones with titles like The Invisibles or lost paradise.

“Crude oil is the most flexible and plastic material I have ever worked with. It has a sweet smell, similar to gasoline, with a texture similar to flowing molasses. But once I draw with her, and after she dries, she no longer smells, ”she said.

Working with crude oil has its advantages, although, says Sokhanvari, it is wise to use protective equipment to do so.

“The practical challenges of my experience are that the brands vary depending on the humidity and the temperature of the room. So I can never predict how the job will end, and of course, as a mutagenic material, it is a very dangerous material to use without gloves and masks. ”

First, she uses a squirrel hair brush and starts with the most diluted oil, working up the layers to the final image. His abstract works also incorporate gold, in pieces intended to represent self-portraits.

The concept, she says, “was based on the idea of my absence from Iran. As I am absent from family events and therefore from family photographs, I draw the negative form between people and objects in family photographs where I should be my self-portraits. These forms made in crude oil testify to my exile from Iran. ”

Again, and especially for an Iranian artist, the material is a message, as well as the image: “The use of crude oil and gold in my art reflects the fact that these two materials are the most precious assets that support the US dollar and hence the most important elements of the global economic recession, “she said.

“An elementary fire”

Roshan still works with his signature medium.

From a valley near Masjid-i-Sulaiman, and sometimes from parents who still work in the company, today he obtains two types of materials to work with: diluted crude oil and petroleum which has hardened on the surface for about 100 years.

The historical maps that form the backdrop to his works, of the oil cities of Abadan or Ahwaz, date from the time of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, founded by the British in 1908 after the discovery of oil in Masjid -i-Sulaiman. He uses oil in the method of “screen printing” (printing with stencils on a fabric mesh) and brewed tea much loved by the Iranians and the British.

Another series of works, Fairyland Awards, comes from short films he made on “oil denial plans”, the colonial powers’ war plans to depopulate the region by poisoning the water supply.

But just because it was close at hand, that doesn’t mean it was easy.

“It is certainly a difficult task,” he wrote, “because I have often painted and finished my work, except for the oil printing and the printing did not go well. The oil may have been too thin or too thick or too hot or too cold… ”

At family gatherings at Roshan’s home, the whole discussion at the table focused on the daily operations of the petroleum industry – with his cousin, brother, uncle and father in the industry, excavations and construction in finance and social services.

In Khuzestan, oil was a ticket to a “glorious and delicious” life compared to many ordinary Iranians, he said – even the bills for electricity, water and gas were covered by the company . Even his first design lessons are free. For oil company marriages, even the payment of the traditional marriage to the mother of the bride, the Shir baha, was abolished.

Now he has made oil a staple of his artistic work, from the strange “scent” of British oil culture, he says, to oil as “an elemental fire” deeply rooted in culture and Iranian literature.

His father, now retired, carried his petroleum identity card in his shirt pocket wherever he went. “I still remember my father’s personal number: 72344,” said Roshan.

“These figures are full of sensation for me; it is a strange nostalgic feeling of our beautiful childhood. And, especially in these difficult and strange days of Iran, they sound like a dream of sleep and remind me of dreams. ”

Amin Roshan’s Fire of Love exhibition is at the small Rossi & Rossi Gallery in London by appointment only until March 27, 2020