The belief that central banks will come to the rescue of the global economy affected by coronaviruses has grown, as the financial fallout from measures taken to try to control the epidemic has become more apparent.

A litany of factory closings, mass quarantines and day-to-day travel bans will almost certainly reverse the modest recovery in global growth that was widely anticipated for this year, with few countries likely to escape their share of the pain.

There is a growing expectation of a so-called global recession, which many describe as growth below 2.5%.

On Monday, the OECD lowered its global growth forecast for 2020 from 2.9% it forecast in November to 2.4%, adding that a “more sustainable and more intensive coronavirus epidemic” could force growth to 1.5% only.

As a result, the markets are now forecasting rate cuts of almost a year and a half at the time of the March meeting of the US Federal Reserve. At the start of the year, the consensus was that even a single cut in 2020 was not a done deal.

The European Central Bank is now priced at a tenth of a percentage point reduction this year, a shift from January’s position when investors began tentatively assessing rate hikes in 2021. Markets are also forecasting more than a drop in the Bank of England this year. , while the Bank of Japan declared itself “well prepared” to ease monetary policy if necessary.

The impact may be very different in large parts of the emerging world, however, some central banks may be forced to prematurely end their monetary easing cycles due to recent market swings related to coronaviruses.

Almost all freely traded emerging market currencies have weakened in recent weeks, as a risk-free trading environment has led investors to fall back on “paradise” currencies like the US dollar and the Swiss franc. Commodity exporting countries were hit twice as oil and metal prices fell against a backdrop of weaker global demand.

The South African rand has led the way, slipping up 11.1% against the dollar this year, although the country has not reported any cases of new coronaviruses so far.

Latin America also recorded a minimum number of confirmed virus cases, but the Brazilian real has fallen 10.8% since the start of the year, as the Chilean peso fell 8.3% and the Colombian peso 7.5%.

The Russian ruble lost 7.6%, the Turkish lira, the South Korean won and the Mexican peso having been sold, among others.

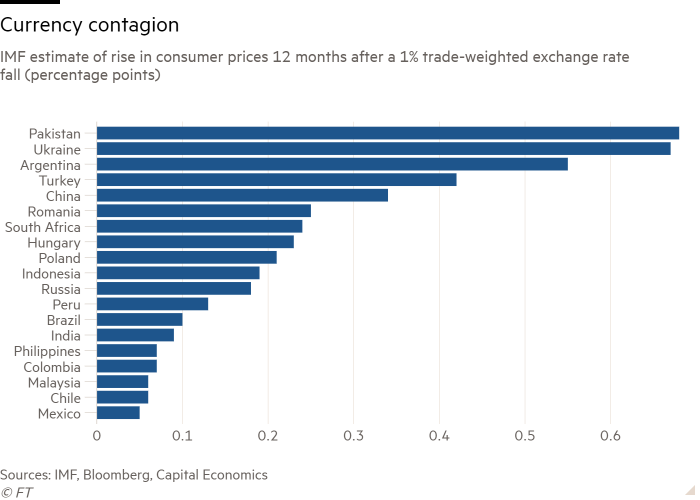

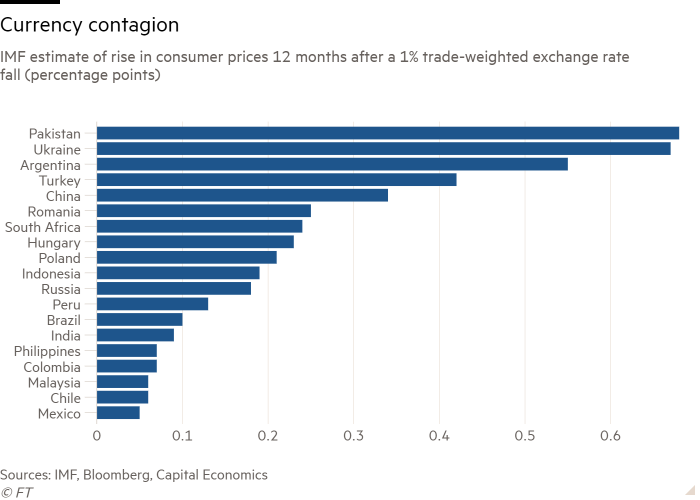

The fall in the currency will cause inflation to rise by raising the price of imported goods and services.

Edward Glossop, emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, predicted that sales would drive inflation up by at least 0.6-0.7 percentage points over the next year in Russia and South Africa. South, reinforcing his opinion that the cycles of monetary easing in the two countries are now “coming to an end”.

This would come even if economic growth is likely to come under pressure, given the duo’s heavy dependence on commodities, the OECD lowering its Russian growth forecast from 0.4 percentage points to 1.2 % and halving its expectations for South Africa to just 0.6%. , well below population growth.

Glossop also noted a similar acceleration in inflation in Turkey, where he believed the central bank would reverse the trend and start raising interest rates in the second half.

Russia, South Africa and Turkey are the most vulnerable among the large emerging economies due to their high rates of currency transmission to inflation, a factor determined by their degree of trade openness, the credibility of the central bank, inflation expectations and the size of their output gap, said Glossop.

Pakistan, Ukraine and Argentina still have higher transmission rates from the weak exchange rate to inflation, according to IMF calculations.

Countries like Poland, Brazil and South Korea are also expected to see inflation rise by at least 0.3 percentage points thanks to the decline in their currencies, with more modest increases in Mexico, Chile , Colombia, Malaysia and the Czech Republic, added Glossop. .

However, the reaction of central banks to higher inflation is likely to vary from country to country.

“Some [such as Mexico] will be scared off by any sign that the weak currency is driving higher inflation. Others, mainly in Asia, will prioritize supporting growth, ”said Glossop.

Other effects may also come into play. The fall in the price of oil, which has dropped 24% this year, will help reduce inflation in many countries, as will lower demand in general.

It can be offset by a series of supply disruptions that could drive up prices in certain product categories.

Global laptop shipments, for example, were likely cut in half in February, according to Trendforce, a Taiwan-based technology research firm.

World prices for garlic and ginger have also increased, due to logistical difficulties in sourcing from China, a major exporter. Japan also reported a sharp drop in vegetable imports from China, its main foreign supplier.

The belief that central banks will come to the rescue of the global economy affected by coronaviruses has grown, as the financial fallout from measures taken to try to control the epidemic has become more apparent.

A litany of factory closings, mass quarantines and day-to-day travel bans will almost certainly reverse the modest recovery in global growth that was widely anticipated for this year, with few countries likely to escape their share of the pain.

There is a growing expectation of a so-called global recession, which many describe as growth below 2.5%.

On Monday, the OECD lowered its global growth forecast for 2020 from 2.9% it forecast in November to 2.4%, adding that a “more sustainable and more intensive coronavirus epidemic” could force growth to 1.5% only.

As a result, the markets are now forecasting rate cuts of almost a year and a half at the time of the March meeting of the US Federal Reserve. At the start of the year, the consensus was that even a single cut in 2020 was not a done deal.

The European Central Bank is now priced at a tenth of a percentage point reduction this year, a shift from January’s position when investors began tentatively assessing rate hikes in 2021. Markets are also forecasting more than a drop in the Bank of England this year. , while the Bank of Japan declared itself “well prepared” to ease monetary policy if necessary.

The impact may be very different in large parts of the emerging world, however, some central banks may be forced to prematurely end their monetary easing cycles due to recent market swings related to coronaviruses.

Almost all freely traded emerging market currencies have weakened in recent weeks, as a risk-free trading environment has led investors to fall back on “paradise” currencies like the US dollar and the Swiss franc. Commodity exporting countries were hit twice as oil and metal prices fell against a backdrop of weaker global demand.

The South African rand has led the way, slipping up 11.1% against the dollar this year, although the country has not reported any cases of new coronaviruses so far.

Latin America also recorded a minimum number of confirmed virus cases, but the Brazilian real has fallen 10.8% since the start of the year, as the Chilean peso fell 8.3% and the Colombian peso 7.5%.

The Russian ruble lost 7.6%, the Turkish lira, the South Korean won and the Mexican peso having been sold, among others.

The fall in the currency will cause inflation to rise by raising the price of imported goods and services.

Edward Glossop, emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, predicted that sales would drive inflation up by at least 0.6-0.7 percentage points over the next year in Russia and South Africa. South, reinforcing his opinion that the cycles of monetary easing in the two countries are now “coming to an end”.

This would come even if economic growth is likely to come under pressure, given the duo’s heavy dependence on commodities, the OECD lowering its Russian growth forecast from 0.4 percentage points to 1.2 % and halving its expectations for South Africa to just 0.6%. , well below population growth.

Glossop also noted a similar acceleration in inflation in Turkey, where he believed the central bank would reverse the trend and start raising interest rates in the second half.

Russia, South Africa and Turkey are the most vulnerable among the large emerging economies due to their high rates of currency transmission to inflation, a factor determined by their degree of trade openness, the credibility of the central bank, inflation expectations and the size of their output gap, said Glossop.

Pakistan, Ukraine and Argentina still have higher transmission rates from the weak exchange rate to inflation, according to IMF calculations.

Countries like Poland, Brazil and South Korea are also expected to see inflation rise by at least 0.3 percentage points thanks to the decline in their currencies, with more modest increases in Mexico, Chile , Colombia, Malaysia and the Czech Republic, added Glossop. .

However, the reaction of central banks to higher inflation is likely to vary from country to country.

“Some [such as Mexico] will be scared off by any sign that the weak currency is driving higher inflation. Others, mainly in Asia, will prioritize supporting growth, ”said Glossop.

Other effects may also come into play. The fall in the price of oil, which has dropped 24% this year, will help reduce inflation in many countries, as will lower demand in general.

It can be offset by a series of supply disruptions that could drive up prices in certain product categories.

Global laptop shipments, for example, were likely cut in half in February, according to Trendforce, a Taiwan-based technology research firm.

World prices for garlic and ginger have also increased, due to logistical difficulties in sourcing from China, a major exporter. Japan also reported a sharp drop in vegetable imports from China, its main foreign supplier.