Debt-strapped Sri Lanka has reached a service-level agreement with the IMF, which promises access to $29 billion over a 4-year period under the institution’s Extended Financing Facility. Considering Sri Lanka’s $51 billion external debt, this sum is extremely small. It also comes with a host of conditions ranging from raising fuel and electricity tariffs to increasing taxation to reduce public deficits – policies that a government with limited legitimacy should have difficult to impose on an economically devastated population.

Still, the Sri Lankan government hopes the deal will be passed by the IMF board, as it is a step forward in convincing foreign creditors and investors to “go back” to the country, which will only increase the burden of its existing external commitments.

But this is by no means the first step towards resolution. Instead, the IMF has conditioned its “assistance” on Sri Lanka persuading its multiple creditors to restructure and reschedule past debt. Bilateral and multilateral official creditors could be on hand to help Sri Lanka. But private bondholders who account for more than 80% of Sri Lanka’s debt to private creditors would be less willing to agree to a deal that would force them to take losses. At least some of them are likely to hold their own.

Ten years ago, in 2012, bondholders accounted for 55% of the stock of long-term debt that Sri Lanka owed to private creditors (Chart 1). Debt to private creditors represented 28% of outstanding long-term debt. But between that year and 2020, when long-term debt outstanding had risen from $26.2 billion to $46 billion, the share of private creditors had risen to 37% and that of bondholders private credit at 84%. This is a major hurdle in finding a way to get the country out of the debt it is currently trapped in.

Generalized problem

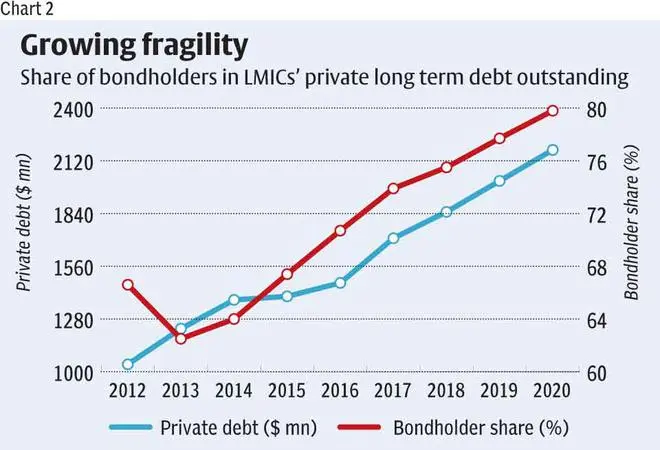

The problem plaguing Sri Lanka is not unique. It is widespread in less developed countries, although it is particularly acute in a few. The stock of long-term private external debt of countries identified by the World Bank as belonging to the low- and middle-income category has more than doubled, from $1,040 billion in 2012 to $2,180 billion in 2020 (graph 2).

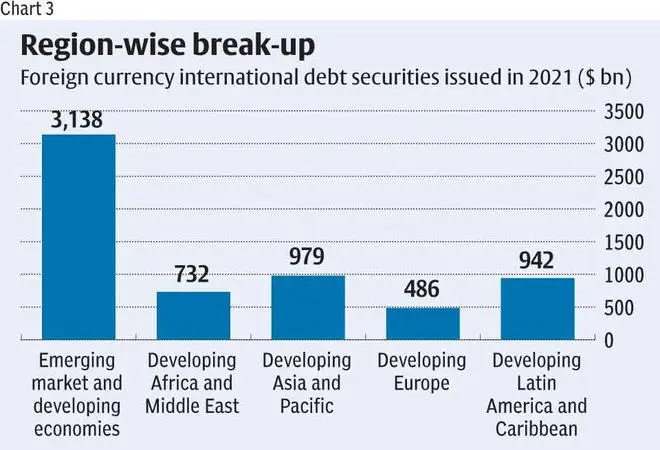

Bondholders’ share of this debt rose from 63% in 2013 to 80% in 2020. Regionally, Latin America and the Caribbean and developing Asia and the Pacific led the way, although in the latter case, the presence of China inflates the total (Chart 3).

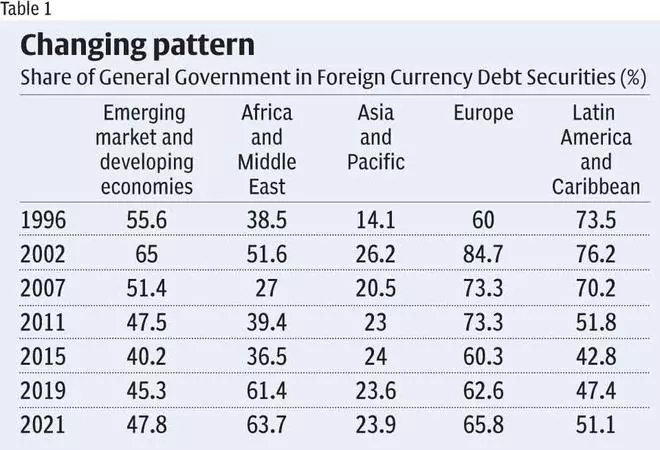

What is remarkable, however, is the variation in government bond borrowing in different regions. Overall, the share of governments in foreign currency bond issuance in emerging and developing economies (EMDE) fell from 65% to 48% between 2002 and 2021, in line with the liberalisation-driven transition to bond-based foreign currency borrowing by private investors. financial and non-financial corporations.

But this fall was largely due to declines in developing Europe (from 85 to 66 percent) and Latin America and the Caribbean (from 76 to 51 percent).

In contrast, the share of public issues has increased in Africa and the Middle East (from 39% in 1996 to 64% in 2021) and in developing countries in Asia and the Pacific (from 14 to 24% over the same years).

Clearly attracted by low interest rates and easier access to bond markets, governments in developing countries have issued foreign currency bonds to finance their spending.

A 2014 IMF report noted: “Sub-Saharan Africa’s access to capital markets is improving significantly. Favorable global financial conditions—low interest rates in advanced economies and low global risk aversion leading to a reallocation of portfolios in search of risk-adjusted returns and diversification opportunities—are facilitating the Access of Sub-Saharan African Countries to International Capital Markets.

“The first or repeat issuance by these countries is also seen by many observers as recognition of the high return potential of sub-Saharan Africa, due to its wealth of natural resources and improved macroeconomic and development prospects.”

But foreign currency bonds may not be the best way to raise resources for a number of reasons. First, unlike domestic currency borrowing, external borrowing requires debt service commitments to be covered in foreign currency.

Over-indebtedness

Any external shock affecting revenue or foreign currency earnings can precipitate over-indebtedness. Moreover, in the event of an unexpected depreciation of the national currency, the cost of servicing the local currency debt would skyrocket and add to the servicing burden.

Moreover, when debt takes the form of bonds, it becomes easily negotiable with significant implications. Since bond issues are done through the market, these issues can be picked up by various investors looking for high yields. These speculative investors are likely to exit at the slightest sign of uncertainty, including in the markets in which they raise their capital.

Thus, the continued effort of central banks in developed countries to raise interest rates and limit or withdraw excess liquidity from money markets triggers an outflow of bondholders from less developed countries. This drives down bond prices and raises interest rates, adding to debt stress. It also increases the cost of incurring new debt, often necessary to service past debt. Finally, as observed in the case of Sri Lanka, if over-indebtedness reaches levels where default is imminent, the presence of several bondholders in the creditor community delays or prevents settlement, some of them waiting for better terms. Sri Lanka has been sued in the United States by bondholder Hamilton Reserve Bank Ltd, which holds more than $250 million of Sri Lankan international sovereign bonds that matured on July 25.

Hamilton owns more than 25% of these bonds and can block any restructuring efforts. This would prolong the period of pain and even make resolution nearly impossible. While borrowing in foreign currency is a “sin” in itself, doing so by issuing foreign currency bonds is courting the devil in the heart of private financial markets.

Despite these problems, the IMF has supported foreign currency bond issues by less developed countries, as long as they are accompanied by “sound” macroeconomic policies. What is missing here is that choosing to issue sovereign bonds in foreign currencies may itself be unwise from a macroeconomic policy perspective.

Published on

September 05, 2022